Introduction: A Necessary Shift

In Northern Uganda, people and nature have long shared a quiet harmony. Trees are more than time, they offer shade, shea nuts, firewood, and echoes of memory. Wetlands are not just water, they are lifelines, nurturing papyrus, filtering streams, and shielding crops from floods. But today, that delicate balance under growing strain. As markets expand and populations rise, the natural systems that sustain life are being stretched to their limits.

Traditionally, conservation and economic development operated in parallel, rarely intersecting. NGOs spoke of protecting forests. Agribusinesses focused on yields and sales. But in my view, that divide is no longer acceptable. Markets are rooted in ecosystems. Without healthy soils, clean water, and a stable climate, no value chain can truly thrive. Ignoring nature is not just bad practice, it is bad economics.

That is why, through the Climate Smart Jobs (CSJ) programme, we are doing things differently. We are rethinking how markets work, not as extractive forces, but as vehicles for restoration. We are supporting business models that value ecosystems not as scenery, but as strategic assets. In my opinion, this shift is not optional, it is the only way we can future-proof livelihoods.

Integrating shea and other tree species within crop gardens promotes a shift from amber to green, enhancing soil health, biodiversity, microclimate regulation and long-term sustainability through regenerative undercropping practices.

Integrating shea and other tree species within crop gardens promotes a shift from amber to green, enhancing soil health, biodiversity, microclimate regulation and long-term sustainability through regenerative undercropping practices.

What We Are Doing On CSJ

At CSJ, we recognised early on that ecosystem services could not be treated as a side issue. They must be central to how we design, support, and scale business models. So, we asked ourselves: what would it look like if nature mattered at every stage of a value chain? Today, the answers are visible across the communities I visit in Northern Uganda.

Take our agroforestry adoption model. Across districts in the northern region, we are supporting farmers to reintroduce trees into their cropping systems, not just any trees, but those that make economic sense. Indigenous tree species for poles and shade, shea for nuts to produce butter, and cocoa for export. Through partnerships with agro enterprises, we help communities access seedlings, training, and markets. The result is a farming ecosystem that feeds families, stores carbon, and protects biodiversity all at once.

Our work with large-scale investors has been particularly eye-opening. We are shifting how they engage, from plantation-style displacement to nucleus-out grower models that respect both the land and its people. We support these investors to think long-term: agroforestry over monoculture, cover crops over bare fields, and community trust over quick profits. And when you sit with these investors and map out the risks, they get it. Nature-smart is business-smart.

Other models build on this principle. From regenerative farming in refugee-hosting areas using minimum tillage, to mechanised land preparation that avoids soil compaction. Every model we support is being reimagined with ecosystem services in mind.

Even our enabling models, which do not directly manage land, play a vital role. Post-harvest excellence reduces food waste and eases pressure to clear new fields. Climate-resilient seed systems promote drought-tolerant, biodiversity-friendly crops. Childcare services free up women’s time, something I’ve come to appreciate deeply, so they can engage in replanting and soil restoration. Insurance helps households avoid selling land when disaster strikes.

Put together, these models paint a picture of markets that support both people and nature.

What We Are Learning from Implementation

One of the biggest things I have come to realise is that integrating ecosystem services into market systems development is not just a technical shift, it is a cultural one. It is about helping people see nature not as a passive background, but as an active system that holds their businesses together.

At the start, most partners did not speak about soil structure, water retention, or biodiversity. Their language revolved around inputs, margins, and yields. And honestly, I understood why, that’s how markets have been framed for years. But when we introduced the concept of ecosystem services and linked poor soils or disappearing pollinators to falling profits, the lightbulbs went on. Farmers began making the connection between compost and crop performance, between mulching and income. That shift in mindset is where real change begins.

Design has also proven critical. Take Mechanisation, for example, it can be destructive or regenerative; it all depends on how it is applied. I have seen it go both ways. But by working with tractor service providers, training them on subsoiling, and introducing conservation implements, we have started to flip what used to be a red flag into an amber and progressively green opportunity.

Perhaps the most humbling lesson for me has been about time. Ecosystem services are easy to overlook when they are working well. But when they fail, the consequences are hard and immediate. This work demands patience. It requires repeated demonstration, trust, and long-term relationships. Embedding ecosystem thinking into how markets operate is not something you can rush. It is something you nurture step by step.

Making Ecosystem Thinking Practical – The dual lens framework (Refer to Annex 1)

As we began integrating ecosystem services across the CSJ business models, it became clear that good intentions were not enough. Saying “nature” matters is one thing, and making it practical is another. We needed a consistent way to assess each model, not just to flag risks but also to spot untapped potential. And we needed a common language that made sense to everyone we work with, from farmers to financiers.

That’s why we suggested the dual-lens framework. It combines a RAG rating to assess ecological risk with an Ecosystem Services Integration Continuum that shows how ambitious a model really is. Together, they help us move beyond compliance and into real transformation. Most importantly, they have helped make ecosystem thinking part of everyday decision-making, not just a side conversation. (see annex I for the framework)

Together, the RAG and Continuum lenses:

- Diagnose ecological risks early

- Tailor technical support

- Guide green investment

- Raise awareness among stakeholders

- Track and reward progress

This flexible framework empowers decision-makers—from farmers to financiers—to make smarter, greener choices without needing to be environmental experts.

What Advice Do We Have for Others?

If you are thinking about how to integrate ecosystem services into MSD, the main advice is, start simple and start now. You do not need perfect data or a team of ecologists. What you need is curiosity, commitment, and a few practical tools.

- Map how your models or innovations depend on and affect nature. Even a basic RAG assessment can reveal key risks or missed opportunities. Ask: How does this model depend on nature? How does it impact it?

- Use the Continuum to guide ambition. Are you just avoiding harm or actively restoring what was lost? Let the Ecosystem Services Integration Continuum help you aim higher.

- Train your partners. Whether they are agro-dealers, processors, or community leaders, help them understand how ecosystem health is good business.

- Reward nature-positive practices. Link these to finance, visibility, or access to new markets.

- Build in feedback loops. Monitor not just yields or profits, but soil health, water use, or tree survival. Let nature’s feedback guide your programming.

Conclusion: Working With Nature is Smart Development

Markets in Northern Uganda and everywhere are only as strong as the ecosystems that sustain them. When soils erode, trees disappear, and water dries up, no amount of financing or innovation can compensate. But when those ecosystems are restored, when trees are planted, soils nurtured, and landscapes healed, everything else becomes possible.

CSJ is showing that we do not have to choose between growth and green. You can and must do both. By working with nature as an ally, we are building markets that are more inclusive, more resilient, and more sustainable.

This is not just about jobs today. It’s about securing the natural foundations that future generations will depend on. Because in the end, working with nature isn’t just good development—it’s the smartest investment we can make.

Annex 1

Making Ecosystem Thinking Practical – The dual lens framework

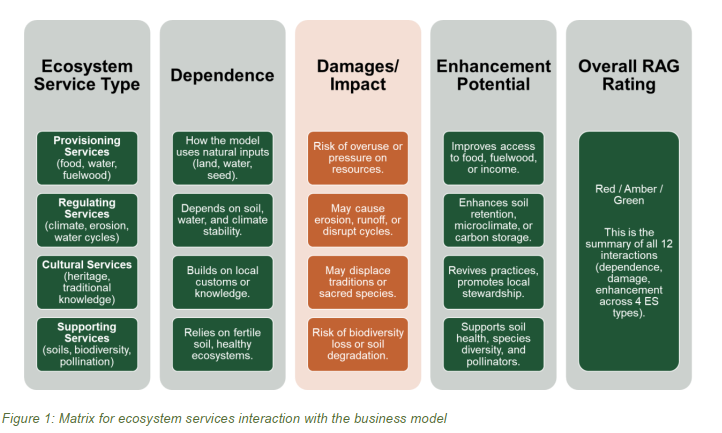

The dual-lens framework combines a RAG rating to assess ecological risk with an Ecosystem Services and Integration Continuum. Together, they help us move beyond compliance and into real transformation. Most importantly, they have helped make ecosystem thinking part of everyday decision-making, not just a side conversation.

1: The RAG Rating System – Understanding Risk and Opportunity

The first lens focuses on three practical questions:

1. How much does the model depend on nature? For example, rain-fed agriculture depends on regular rainfall, healthy soils, and pollination. Agroforestry depends on tree survival and biodiversity. If nature falters, these models collapse.

2. How does the model impact nature? This could be through soil degradation, deforestation, overgrazing, chemical use, or unsustainable water extraction. It could be slow and invisible, like nutrient depletion, or fast and obvious, like cutting down a shea tree.

3. Does the model enhance nature in any way? Are there activities that regenerate the land, such as mulching, composting, tree planting, or pasture conservation? If so, these are not just green practices; they are investments in the future viability of the market system.

Based on these questions, each model is scored using a simple traffic-light logic:

• Red: High ecological risk. These models degrade ecosystem services, either directly or through neglect. Mechanised land preparation, for instance, was rated Red in our early assessments due to the risk of soil compaction, topsoil loss, and increased erosion. Left unchecked, these impacts could undermine food security and income in the medium term.

• Amber: Moderate risk or missed opportunity. These models may be environmentally neutral or inconsistent, depending on how well they are implemented. For example, regenerative farming using minimum tillage and compost can restore soil health, but only if farmers apply the full package correctly. Poor training or missing inputs can make it just another farming method with marginal benefits.

• Green: Low risk and nature positive. These are models that not only depend on ecosystem services but also actively help to maintain or enhance them. Our Agroforestry model (including shea revitalisation) was rated a Green, thanks to its emphasis on tree conservation, traditional ecological knowledge, and linkage to carbon markets. It is a model that sees standing trees as assets, not obstacles.

The RAG system does not just rate, it helps us act. Red models trigger redesigns. Amber ones require technical support, training, or bundling with greener practices. Green models help us demonstrate what is possible and guide investment.

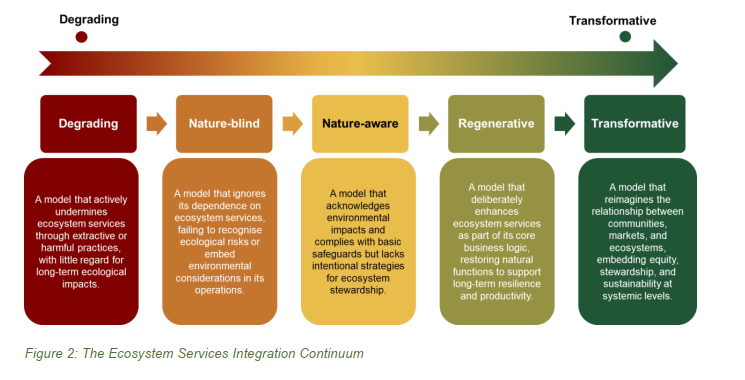

2: The Ecosystem Services Integration Continuum – Understanding Ambition and Intent

While the RAG system tells us where a model is right now, the Integration Continuum helps us understand its direction of travel. Is it simply trying to avoid harm, or is it trying to change the game?

We classify models into five stages:

1. Degrading: These business models are actively harming nature. Land clearing for short-term gain, unchecked pesticide use, or overgrazing without pasture planning, all fall here. These models are extractive, driven by immediate results but ignoring long-term costs.

2. Nature-blind: These models do not necessarily destroy ecosystems, but they do not factor them in either. A trader moving agricultural produce may seem neutral, but if their work indirectly encourages poor farming practices or tree cover loss, they become part of the problem. Natureblind models operate on the assumption that ecosystems are infinite and free.

3. Nature-aware: These business models recognise that nature matters. They may comply with environmental rules, set aside buffer zones, or avoid ecologically sensitive areas. But they often stop short of active restoration. Their sustainability efforts are reactive or externally driven, more compliance than conviction.

4. Regenerative: Here, ecosystem services are built into the core business logic. These models invest in soil health, plant trees, retain groundcover, restore watersheds, and support pollinators, not just for goodwill, but because these actions make business sense. Regenerative farming, shea parkland restoration, and agroforestry all belong here.

5. Transformative: These are the game changers. They don’t just restore nature, they reimagine how markets, communities, and ecosystems relate. They embed indigenous knowledge, shift gender dynamics, redesign incentives, and support policies that reward ecosystem stewardship. A transformative model might include a shea-based payment for ecosystem services scheme, codesigned by women, elders, and traders, where protecting sacred groves is rewarded with income and pride.

Why The Dual-Lens Framework Matters

When combined, the RAG system and the Continuum offer a full picture. RAG shows us the model’s current ecological footprint. The Continuum shows us the model’s ecological ambition.

For example, block farming could start off as Degrading (clearing communal land without planning) and Red (high risk of erosion), but with adjustments, minimum tillage, crop rotation, and communal governance, it could move toward Regenerative and Amber. Eventually, it might even reach Green and Transformative if it reshapes land tenure and promotes shared environmental responsibility.

By applying this framework, we have been able to:

- Diagnose risks early, before scale-up causes damage

- Tailor technical support where it’s most needed

- Guide investment toward models that offer ecological returns

- Raise awareness among private actors and implementers

- Track progress and reward improvement over time

It is a flexible tool, and that is the point. Whether you are managing agroforestry investments, promoting goat value chains, or supporting agri-SMEs, the framework helps you make smarter, greener decisions without needing to be an environmental expert.